Ready for more Civil War? Of course you are! Everyone loves the Civil War! It was so Civil. And so warry.

Ready for more Civil War? Of course you are! Everyone loves the Civil War! It was so Civil. And so warry.

Okay, now for part II of the interview. Charge!!!!!!!!!!

AARON: In the West, which side would you have wanted to fight on? Don’t worry, if you say Confederates we won’t say you’re racist. We’ll just think it.

Quinn: The Coloradans, no question. Come on, Aaron: no real Coloradan shoulders arms so that Texans can overrun our state—we have real-estate agents for that.

AARON: What would have been the worst part of fighting in the Civil War? The drab uniforms? The bad coffee? Dysentery?

Quinn: Probably everyone agrees that dysentery is worse than chicory coffee (I’d say that everyone agrees, but people are strange …), and chicory coffee (made from ground, roasted endive roots, chicory coffee was more-readily available than the real thing—especially to Southern troops later in the war, as the Union’s naval blockade curtailed imports of every kind) is—in my opinion—worse than a drab uniform. And besides, early in the war some regiments wore hilariously theatrical uniforms (the 11th New York Infantry Zouaves spring to mind—their uniforms were patterned on those worn by French colonial troops in Algeria: gray MC Hammer-pants with red and blue trim, leather leggings, red fezzes, etc.).

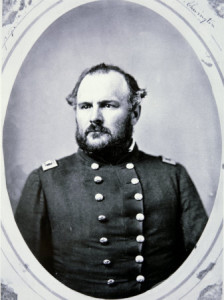

Seriously, though? As in any war, many men struggled with the emotional toll of killing other humans. Even those who believed in the correctness of their cause, or those whose church leaders had exempted them from normal strictures against killing, struggled to process the things they’d done (speaking of which, Lord, you wouldn’t believe the contortions some religious leaders went through to justify the wholesale murder taking place within their parishes). Of course, back then there was no such term as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder—rather, men unhinged by the war were said to have a “soldier’s heart.” This legacy of violence, coupled with residual bitterness between barely-reconciled veterans, accounts for much of what made the West wild in the decades after the war. Men who’d killed dozens or even hundreds at Antietam, Shiloh, or Franklin, were less likely to show restraint during barroom brawls in Dodge City, Bodie, or Bannack. John Potts Slough, for example (the temperamental commander of Union forces at Glorieta Pass and a major supporting character in my novel)—who received a patronage appointment after the war as postmaster of Santa Fe—was shot dead during an argument with a political rival in the lobby of the La Fonda Hotel.

Other miseries? Lice. Smallpox. Loneliness—missing family and friends. Boredom, too. Boredom intercut with horrifying violence, as the Civil War marked a turning point in the scope and scale of warfare: 18th Century tactics were pitted against modern weapons (e.g., frontal charges with bayonets against entrenched enemies with rifled muskets and artillery), and the weapons won. The killing was almost without precedent. Indeed, European observers were so impressed by Confederate entrenchments at Petersburg, VA, that early in World War I, military thinkers revisited their doctrines and decided that trench warfare was the way to go (trenching by South Africa’s Boers also fired the British military’s imagination). And of course, back then, soldiers marched everywhere: a) Sibley’s poorly-supplied Texans marched 800 miles from San Antonio to Santa Fe (farther than Napoleon’s epic march on Moscow)—and back, with their supplies in even worse condition; and b) the First Colorado Regiment marched 300 miles from Denver City to Fort Union in 13 days—they averaged a marathon a day, despite being struck twice by blizzards. Push comes to shove, probably everything about fighting in the Civil War was miserable.

AARON: What was the best book you read in preparation of your novel, best hike, best coffee shop you wrote in? Best one thing?

Quinn: Best Book: the best non-fiction book I read while researching was Don E. Alberts’s The Battle of Glorieta, Union Victory in the West. It is well written and well annotated, and while several books on the subject indulge in apocrypha, Mr. Alberts sticks to facts. Best fiction was re-reading Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, and while it’s about World War I instead of the Civil War, it reminded me how grim humor functions in wartime.

Quinn: Best Book: the best non-fiction book I read while researching was Don E. Alberts’s The Battle of Glorieta, Union Victory in the West. It is well written and well annotated, and while several books on the subject indulge in apocrypha, Mr. Alberts sticks to facts. Best fiction was re-reading Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, and while it’s about World War I instead of the Civil War, it reminded me how grim humor functions in wartime.

Best Hike: The Indian Creek Trail in New Mexico’s San Mateo Mountains. New Mexico Highway 107 strikes south from the town of Magdalena and more or less follows the route of the Texans’ retreat from the debacle at Peralta. Indian Creek is more or less where I imagined my fictional Confederates taking a wrong turn and dooming their escape. I hiked there in April once, and even that early in springtime, already it was awfully hot, dry, and windy, which pretty much set the tone for Glorieta’s ending.

Best Place to Write: Apart from my home office, where all the heavy lifting gets done, the two places I most enjoyed working on Glorieta were: a) New Mexico’s highways—I didn’t write while driving, but I did keep a digital recorder handy and narrated the sights as I went; and b) Evengelo’s Lounge, 200 West San Francisco St Santa Fe, NM 87501. The owner, Nick Evengelo, is someone everyone should meet—a total character, but decent and kind. I sat at Nick’s bar on a cold, quiet January night, and he kept the drinks coming and inquired occasionally to see how the writing was going. Very well, as I recall, or at least until those drinks kicked in. Very happy memories of that place.

AARON: What is the best story that didn’t make it into your novel, or did all the great stories make it in?

Quinn: A lot was cut, condensed, or simply faded away from the first draft to the final, but I think that everything truly essential survived. I cut a good bit of the Coloradans’ (i.e., the fictional miners who enlisted just before the First Colorado Regiment set off for New Mexico) back-story, and I think they seem a little weird as a result, but I really didn’t want to go over 500 pages or chop the story into halves. Other stories were cool but didn’t directly advance the plot, so these, too, were cut: at one point, historic Central City figures Aunt Clara Brown and Mary York—one black and the other white, but both fugitives from slavery—helped my fictional miners in their flight from crooked justice; and I compressed a section on the Taos Rebellion—which spread far beyond Taos—so that only events affecting one antagonist’s family were retained. Also, I moved a great deal of biographical information about actual persons, including their post-war lives, to my websites, quinnkaysercochran.com (and/or westlandbooks.com.)

AARON: Why do you think the Civil War in the West is such a “hidden” story?

Quinn: I think there are several reasons. The first is scale: relatively minor battles back East involved thousands, even tens of thousands of combatants; at Glorieta, Valverde, and Peralta, there were never—even with both sides combined—more than 3,500 men on those fields, and by far these were the largest battles in the far West (remember, in mid-19th Century America, Missouri, Kansas, and Iowa were considered “west”. The Mississippi River was a de facto West Coast—anything farther was Terra Incognita). The westernmost cavalry skirmish (i.e., between actual soldiers and not partisans) of the Civil War, near Picacho Peak west of Tucson, involved about twenty men on each side—small wonder only diehards and history buffs know about it. Cataclysmic events at Cold Harbor, Fredericksburg, and Manassas deserve more attention simply because of the numbers involved, and because their outcomes had a far greater impact on the war’s result.

The idea that Confederate victory in New Mexico could have turned the entire war in the South’s favor is a stretch. They simply didn’t have enough men or matériel to execute their plans. Had the Texans conclusively won at Glorieta (they did win, but had gained little, left their enemy largely intact, and had to retreat once they discovered that Union raiders had destroyed their supply train), they would have continued toward Fort Union, likely under harassment from Union troops, and found it stripped of supplies. Even if they’d reached Colorado and seized its mines, there’s no conceivable way they could’ve made it then to Salt Lake City (at that time, there was no road through the Rocky Mountains—they would have had to go out of their way north through Wyoming). And west to Los Angeles—where they planned to rally the secession-minded populace and seize its port—the conditions were at least as difficult. Really, their whole enterprise was doomed from the outset.

Another reason few people know about these battles is that they occurred in isolation. Even today, events in the Midwest and West receive comparatively slight coverage in the national press—if anything, in 1862 this disparity was even greater. Huge battles (20,000+ combatants) in Arkansas and Missouri were hardly noticed in New York City, Philadelphia, and Boston, and of course Washington, D.C., Richmond, VA, and Charleston, SC, were front-line cities with problems of their own—people there didn’t have time to notice rather minor events in the far West. Isolation from Eastern population centers also meant less documentation in the press—less of a paper trail for historians and researchers to follow—so the perpetual analysis that accompanies most Civil War events does not occur.

Finally, most history books don’t consider the many Western Indian wars concurrent with the Civil War as part of the Civil War, though surely they were. A partial list includes the Snake War in Idaho, Oregon, and California; the Dakota War, which roiled Minnesota and Iowa; and the proxy war fought between tribes exiled to Indian Territory (today’s State of Oklahoma. How’s that for wretched irony? Tribes expelled from the North and South fought against each other on behalf of their former homelands …). All these conflicts drew men and resources away from Eastern campaigns—who knows what might have resulted had they been deployed there instead? The best non-fiction book I have found that treats the West as a theater of the war is Alvin Josephy’s The Civil War in the American West.

Even here in Colorado, the Battle of Glorieta Pass is largely unknown, which is odd, given that we supplied the troops that helped turn back a Confederate invasion of New Mexico Territory. However, in 1864, less than two years after the heroics east of Santa Fe, John Chivington led the First Colorado Regiment against an Indian encampment on Sand Creek in eastern Colorado Territory. Primarily women, children, and the elderly (most fighting-age men were away hunting), these Indians had camped at the U.S. government’s instruction, and flown both U.S. and white flags to signify their peaceful and cooperative intentions. At first, resulting slaughter was hailed as a great victory, but once stories about the camp’s true nature and body parts from desecrated corpses began circulating in Denver, the scandal that erupted resulted in Congressional inquiries, the murder of a witness before he could testify, and disgrace for the perpetrators. Indian tribes previously disposed to be neutral or friendly toward white settlers no longer trusted the U.S. military, and in no small way, this led to the really awful Indian wars that erupted once the Civil War concluded. All of this is rather heavy for fourth graders, which is the level at which most American schoolchildren learn their state’s history. Ergo, here as much as anywhere, hardly anyone knows about what happened at Glorieta.

Even here in Colorado, the Battle of Glorieta Pass is largely unknown, which is odd, given that we supplied the troops that helped turn back a Confederate invasion of New Mexico Territory. However, in 1864, less than two years after the heroics east of Santa Fe, John Chivington led the First Colorado Regiment against an Indian encampment on Sand Creek in eastern Colorado Territory. Primarily women, children, and the elderly (most fighting-age men were away hunting), these Indians had camped at the U.S. government’s instruction, and flown both U.S. and white flags to signify their peaceful and cooperative intentions. At first, resulting slaughter was hailed as a great victory, but once stories about the camp’s true nature and body parts from desecrated corpses began circulating in Denver, the scandal that erupted resulted in Congressional inquiries, the murder of a witness before he could testify, and disgrace for the perpetrators. Indian tribes previously disposed to be neutral or friendly toward white settlers no longer trusted the U.S. military, and in no small way, this led to the really awful Indian wars that erupted once the Civil War concluded. All of this is rather heavy for fourth graders, which is the level at which most American schoolchildren learn their state’s history. Ergo, here as much as anywhere, hardly anyone knows about what happened at Glorieta.

In my novel, I tried to make John Chivington as complex as I could without excusing his numerous flaws. By all accounts, he was a good family man (aren’t they always?) who hated slavery, and who, prior to Sand Creek, usually sided with right against wrong. He could also be calculating and bombastic—his was the only opinion that mattered. From historic documents and contemporary writings, I couldn’t fully discern his relationship with the First Colorado’s first colonel, John P. Slough. After the war, he defended Slough’s leadership at Glorieta, though this may have been politically motivated revisionism. Certainly, the First Colorado was riddled with feuds, large and small, so it’s not hard to imagine that these two outsized personalities had theirs, too. As well, Glorieta Pass and Sand Creek may be viewed as halves of a whole, at least where Chivington is concerned. At Glorieta, he led a raiding party intent on flanking the Confederates’ main thrust eastward from Santa Fe. Instead, they overshot their goal, stumbled upon the Texans’ lightly guarded supply train, and destroyed it, which forced the Southerners into retreat. At Sand Creek, it’s possible he had the same mindset: knowing that the Indians’ fighting forces were absent and seeing the lightly defended encampment as a supply base for hostiles (nevermind that the tribes in question had foresworn violence), he destroyed the camp, believing that he was forcing a potential threat to withdraw. Who knows? Whatever his thinking, he made himself a pariah even to this day.

AARON: If you had a time machine that could only take you back to the 1860’s, where would you go and why?

Quinn: Any one of several mining camps in Nevada: Treasure City in White Pine County, Austin in Lander County, or Virginia City on the Comstock. Just to see a mining rush of that era at its zenith—can’t really explain why, other than to concede that I’m weird. In Roughing It, Mark Twain tells a story about how Virginia City came to a standstill as the sun set beneath heavy clouds, spotlighting an American flag that flew from the top of Mount Davidson, west of town. There was a buzz on the streets, as people who saw this phenomenon took it as an omen, not knowing that Union forces had just turned back Robert E. Lee’s invasion of the North at Gettysburg, PA, or that Vicksburg, MS, had just fallen to U.S. Grant’s Army of the West (again, see what was considered “west?”). However, Twain being Twain, who knows if this was several events conflated for effect, or for that matter if it was entirely fabricated? Either way it’s a good story—but it sure would be fun to see for myself.

Thanks, Aaron, for this opportunity to ramble about things oddly near and dear to my heart.

Thank you, and yeah, I’ll pass on the chicory coffee roasted endive roots? We shan’t be seeing that in Starbucks any time soon!

Ready for more Civil War? Of course you are! Everyone loves the Civil War! It was so Civil. And so warry.

Ready for more Civil War? Of course you are! Everyone loves the Civil War! It was so Civil. And so warry.

Quinn: Best Book: the best non-fiction book I read while researching was Don E. Alberts’s

Quinn: Best Book: the best non-fiction book I read while researching was Don E. Alberts’s

Even here in Colorado, the Battle of Glorieta Pass is largely unknown, which is odd, given that we supplied the troops that helped turn back a Confederate invasion of New Mexico Territory. However, in 1864, less than two years after the heroics east of Santa Fe, John Chivington led the First Colorado Regiment against an Indian encampment on Sand Creek in eastern Colorado Territory. Primarily women, children, and the elderly (most fighting-age men were away hunting), these Indians had camped at the U.S. government’s instruction, and flown both U.S. and white flags to signify their peaceful and cooperative intentions. At first, resulting slaughter was hailed as a great victory, but once stories about the camp’s true nature and body parts from desecrated corpses began circulating in Denver, the scandal that erupted resulted in Congressional inquiries, the murder of a witness before he could testify, and disgrace for the perpetrators. Indian tribes previously disposed to be neutral or friendly toward white settlers no longer trusted the U.S. military, and in no small way, this led to the really awful Indian wars that erupted once the Civil War concluded. All of this is rather heavy for fourth graders, which is the level at which most American schoolchildren learn their state’s history. Ergo, here as much as anywhere, hardly anyone knows about what happened at Glorieta.

Even here in Colorado, the Battle of Glorieta Pass is largely unknown, which is odd, given that we supplied the troops that helped turn back a Confederate invasion of New Mexico Territory. However, in 1864, less than two years after the heroics east of Santa Fe, John Chivington led the First Colorado Regiment against an Indian encampment on Sand Creek in eastern Colorado Territory. Primarily women, children, and the elderly (most fighting-age men were away hunting), these Indians had camped at the U.S. government’s instruction, and flown both U.S. and white flags to signify their peaceful and cooperative intentions. At first, resulting slaughter was hailed as a great victory, but once stories about the camp’s true nature and body parts from desecrated corpses began circulating in Denver, the scandal that erupted resulted in Congressional inquiries, the murder of a witness before he could testify, and disgrace for the perpetrators. Indian tribes previously disposed to be neutral or friendly toward white settlers no longer trusted the U.S. military, and in no small way, this led to the really awful Indian wars that erupted once the Civil War concluded. All of this is rather heavy for fourth graders, which is the level at which most American schoolchildren learn their state’s history. Ergo, here as much as anywhere, hardly anyone knows about what happened at Glorieta. So, I’m finally off the road. My book has been out about nine months and I’ve been pounding the pavement, harassing people of all socio-economic classes. Those with tattoos and those without. Please, my friend, buy my book. Why you no buy my book? Is good book for you!

So, I’m finally off the road. My book has been out about nine months and I’ve been pounding the pavement, harassing people of all socio-economic classes. Those with tattoos and those without. Please, my friend, buy my book. Why you no buy my book? Is good book for you! Quinn: I will list the differences first. 1) Next time, I will submit an ironclad manuscript. Amazon.com’s CreateSpace platform allows authors to make revisions as they go (however, fees are charged after the first couple uploads), which, for me, is like providing additional rope with which to hang myself. I’ve never read anything, anything I’ve written without wanting to make changes, so this got me into trouble—probably added three months to the process. 2) Next time from the start, I will have a fully developed marketing plan. Hard to believe that I was caught off guard at the end of an eight-year process, but it’s true. For a long time, publication was just a concept—something that might happen on some unspecified date way in the future—and I confess that I didn’t draft a proper business plan in advance. Now I’m flying by the seat of my pants and, I would guess, achieving half as much for twice the work. Had to scramble to build a website, launch a Twitter account, etc. It’s all rather exhilarating, but that’s one of the tradeoffs with self-publication: more of the reward for all the risk (and work). Best advice I would have for other DIY’ers is to network like crazy. Find others who have gone before you and are willing to offer advice, friendly criticism, etc. Think of your book as a small business and remember that just like a business, those without goals and plans usually fail to achieve them. And finally, 2.5) I will have more focus. I took about eight or nine years to write Glorieta, in part because I occasionally set it aside for no particular reason. Not for work, my children, or life events, though at various points I did set writing it aside for those reasons, but because I lacked the discipline to stick with it. The book I’m working on now—a political drama set in an early-twentieth century company-mining town—has its own peculiar challenges, but at least I’m getting better about routinely appearing in front of the keyboard.

Quinn: I will list the differences first. 1) Next time, I will submit an ironclad manuscript. Amazon.com’s CreateSpace platform allows authors to make revisions as they go (however, fees are charged after the first couple uploads), which, for me, is like providing additional rope with which to hang myself. I’ve never read anything, anything I’ve written without wanting to make changes, so this got me into trouble—probably added three months to the process. 2) Next time from the start, I will have a fully developed marketing plan. Hard to believe that I was caught off guard at the end of an eight-year process, but it’s true. For a long time, publication was just a concept—something that might happen on some unspecified date way in the future—and I confess that I didn’t draft a proper business plan in advance. Now I’m flying by the seat of my pants and, I would guess, achieving half as much for twice the work. Had to scramble to build a website, launch a Twitter account, etc. It’s all rather exhilarating, but that’s one of the tradeoffs with self-publication: more of the reward for all the risk (and work). Best advice I would have for other DIY’ers is to network like crazy. Find others who have gone before you and are willing to offer advice, friendly criticism, etc. Think of your book as a small business and remember that just like a business, those without goals and plans usually fail to achieve them. And finally, 2.5) I will have more focus. I took about eight or nine years to write Glorieta, in part because I occasionally set it aside for no particular reason. Not for work, my children, or life events, though at various points I did set writing it aside for those reasons, but because I lacked the discipline to stick with it. The book I’m working on now—a political drama set in an early-twentieth century company-mining town—has its own peculiar challenges, but at least I’m getting better about routinely appearing in front of the keyboard. Quinn: Glorieta really began as a college paper. Years later, it became a screenplay when a friend in TV production suggested I write one. Screenplays are peculiar things with lots of formatting quirks and industry-specific rules, and I tried really hard to make mine conform to those standards (as best I understood them, anyway, given that I was teaching myself as I went, far removed from the filmmaking capitals of New York and California). An agent I worked with said that she liked it, but also that it was too literary and therefore needed changes. Well, I thought that already the story had changed to conform to rules I did not fully understand, so I decided instead to turn Glorieta into the book it wanted to be. As for the 120-page question (there’s one of those rules: one page of script equals one minute of film—120 pages/minutes is the standard. Well-knowns can break this rule; unknowns cannot), within my 120-page screenplay was 90 pages of story, and I was simply unable to say what I really wanted to in so limited a space.

Quinn: Glorieta really began as a college paper. Years later, it became a screenplay when a friend in TV production suggested I write one. Screenplays are peculiar things with lots of formatting quirks and industry-specific rules, and I tried really hard to make mine conform to those standards (as best I understood them, anyway, given that I was teaching myself as I went, far removed from the filmmaking capitals of New York and California). An agent I worked with said that she liked it, but also that it was too literary and therefore needed changes. Well, I thought that already the story had changed to conform to rules I did not fully understand, so I decided instead to turn Glorieta into the book it wanted to be. As for the 120-page question (there’s one of those rules: one page of script equals one minute of film—120 pages/minutes is the standard. Well-knowns can break this rule; unknowns cannot), within my 120-page screenplay was 90 pages of story, and I was simply unable to say what I really wanted to in so limited a space.